Megan Henderson's Many Songs for the Spirit

Many of you know and love Megan Henderson from her work as a pianist with Winsor Music's concert series and outreach program. We're so pleased to introduce her to you anew as a composer (although anyone involved in the Boston-area Shape Note community has known this side of her work for many years)! She has composed a new Song for the Spirit, "With Grace We Meet our Trials" or "Jewell Hill" for our concert on October 4, where she will be sharing the program with her former conservatory professor, John Heiss, as well as music of Boccherini and Schumann.

Megan Henderson is a graduate of the New England Conservatory and has been the adult music director at Payson Park Church since 2010, serving as organist and adult choir director. Megan is a member of the Schola Cantorum of Boston and has made numerous recordings with the Boston Camerata. In addition, she is also active as a pianist and piano teacher in the Boston area. She is on the staff of the Harvard Summer and Extension schools and Village Harmony Summer Camp. She has traveled and performed as a singer throughout the UK and Northern Europe with Northern Harmony, a group that specializes in World Folk Music.

What started the process of writing this Song for the Spirit?

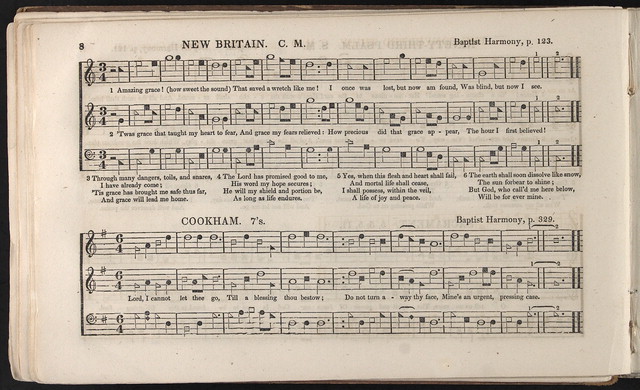

I’ve been interested in Shape Note music for a long, long time, and have been experimenting with the various forms. One predominant form is known as the fuguing tune, which is where you have a homophonic first section, and then a miniature "fugue" to follow.

Can you explain what a fuguing tune is?

It’s not the traditional fugue that Bach would have written, but it does involve the voice parts entering one at a time with the theme or a variant of the theme.

So something like a canon?

Yes! Something like a canon, but canons are the exact same theme coming in at different times.

And where does the text come from?

The words for the fuguing part of this tune come from John Leland, who composed the text for a song called “Ecstasy,” which is in the Sacred Harp [collection of shape note songs], but it seems that his words were loosely based on Psalm 55. I wanted to change the surrounding text of Leland’s chorus, so I composed my own words for the A section to reflect my beliefs about the spirit.

As far as I understand, that’s fairly common to modern-day Shape Note singing, that it’s not necessarily tied to religious observance, practice or belief, but that the singers map their own beliefs or philosophies onto the hymns.

That’s interesting, I hadn’t thought of it that way. There is definitely a resurgence of composers writing in the shape note form. More often, people are using pre-existing texts but getting experimental with the harmonies and the meters.

And are you getting experimental with harmonies?

A bit, yes! I also mess around with the meters from time to time as well.

Have you composed much before this that you’ve released publicly? Personally, I’ve seen things that you’ve written, but have you published or offered your work up for performance?

Well, yes. Most of what I’ve written has been performed by various groups under the Village Harmony umbrella. I’ve been writing in this style for many years now, in this short form. I did write one larger scale called “The Police Log” which is based on the crimes that are listed in the newspaper in Hancock, New Hampshire. The Police Log in Hancock cites such heinous things as a dog digging up somebody’s garden, nothing much more serious than that. That project (commissioned by Jody Simpson) was a lot of fun.

Is that available for public consumption?

I could arrange for that to happen, actually, yes. I also have a piece called "Gordon" that just came out on a new recording by a wonderful group called the Starry Mountain Singers. My pieces are scattered around the internet here and there and on various recordings.

Do you remember the first piece you composed? When did that happen?

Yeah, it was in 1991, when I had broken my wrist — I’m a pianist by training, so the broken wrist put a damper on things, so to speak. I’d been singing Shape Note music for about two years and had gone on a few of trips to England, singing with a group from Vermont that did mostly Shape Note music. I was really fascinated by this style of music, and since I couldn’t play, I decided, alright, I’m going to try to do a little writing. When I first started that in 1991, about six pieces came out right away. They were all based on texts that I really loved and tried to set in my own way with my own style. I’d never written before that. It was surprising to me to find how intrigued I was by the writing process.

How did you get involved with Shape Note singing?

I was singing a concert with my Schola Cantorum in Stratford, Vermont, and a friend in the group had another friend in Vermont who was very involved in the Shape Note community, named Larry Gordon. Larry came to the concert and he and I hit it off and started doing Early Music projects together. Then he introduced me to Shape Note music and I’ve been involved with it ever since then.

There seems to be a link between Shape Note music and Early Music - there are some famous examples of cross-over recordings and performances by Early Music groups. Why do you think that people who are drawn to Early Music have such a draw to Shape Note as well? What is the connection there?

There are similarities in the stark harmonies for starters. Whatever your beliefs are, the spirituality in both of those forms of music is visceral and seems to deeply affect people whether they have a spiritual practice or not. Then there is the “fuguing” aspect, which is connected to the contrapuntal music which you find a lot in Renaissance music. The Boston Camerata and Anonymous Four are good examples of groups that have delved into both genres. I sang on some Shape Note recordings also with the Boston Camerata, and their approach is a little more polished than what my friends in Vermont tend to do in terms of performance practice.

Right; that’s another thing I wanted to ask you about. You are a (very) classically trained musician and pianist, and we at Winsor primarily know you through that kind of work. Shape Note has a very distinct vocal style which is not what a lot of people would consider “classical,” so I am wondering what it’s like for you to move between those two styles, especially as a singer. I know you also sing with Schola Cantorum of Boston and other vocal groups.

I thought you’d never ask! What instantly drew me about Shape Note music was the raw power and energy it has. Having had conservatory training, I was thrilled to see how uninhibited one could be in singing music. When I first started singing Shape Note music with people in Vermont, many of them were [musically] illiterate, but sang with such spirit and such heart; that was what really excited me about that kind of music. There’s not much similarity between singing Thomas Tallis and singing Jeremiah Ingalls, for instance… there’s a lot more chest voice in Shape Note singing and what they like to call the “hard-edged sound,” but in terms of the way I’ve been writing Shape Note music, I don’t tend to write pieces that are meant to be sung at the top of one’s lungs.

That answers my next question, which is: given that this Song for the Spirit is an audience participation portion of the program, and we are not going to be in the traditional square*, how do you intend this piece to be sung? How has our layout of the audience facing the musicians influenced your approach to writing a Shape Note piece?

I also am straying from the original Shape Note form in that, traditionally, Shape Note has the soprano and tenor line doubled up and down the octave. Mine is not meant to be sung that way. It’s really written in standard SATB form, so that’s how we’re going to sing it. The other way that I’m expanding my take on Shape Note music is by putting the melody in the alto line. As an alto myself, this is blatantly selfish! The alto line was usually written last in shape note music and was always by far the most boring line. I'm trying to correct to make that up to my fellow altos! I do also think there's a richness that comes with the melody in a lower register though. It’s probably more fair to say that this piece is written in the Shape Note style, rather than the Shape Note tradition, because of the text that I borrowed from the Shape Note “oevre” and the fuguing tune at the end. But I actually have been questioned: “Why are you even calling it Shape Note music?"

I would just like to point out that the neglect of the alto line is not only true of Shape Note music, that’s also true of traditional hymnody and results in the same problem. We altos are the filler!

Right! I want an interesting alto line, and hopefully with this piece, each line is interesting. I think that’s another real similarity between really intriguing Shape Note pieces and Renaissance music... every line stands beautifully on its own.

Well, not to repeat the question, but you’ve said that the fuguing device is Shape Note, the words are Shape Note, but other than that — because we won’t be in a square*, because we won’t be using that particular vocal technique, because the four part writing is distinctive — what about the piece makes it a “Shape Note piece” as opposed to a piece that uses Shape Note elements?

Visually, the audience will see that it is written in the traditional shapes. Also, the homophonic opening and the "fugue" that follows qualify the piece for that genre. The spiritual nature of the text is also standard fare for the Shape Note style.

So the spirituality of the song is what defines it as Shape Note, because Shape Note is so clearly spiritual?

Writing music, and writing in this style, has been my way of trying to express my own spirituality, which is why I chose to write the text for the first half of this song. I am trying to find ways to secularize spirituality, which I think is appropriate for our time. A lot of people are seeking spiritual direction and nourishment. This is not an easy planet!

What I really wanted to explore in this song was the issue of trust, and hopefully that will be reflected in the text. I was trying to find a way to express my connection to something bigger than myself in a way that more people could relate to. I’m a church musician, and it’s a fact that religious institutions are struggling to keep their membership up. For me, I think it’s so important to live with some sort of spiritual connection. I find it a lot in nature and have set texts in praise of the natural world. I am interested in trying to find and nurture what keeps us strong and gets us out of bed every day...being kind to other people, doing the best we can do here and at the same time sometimes longing for wings to "fly away and be at rest." I think most of us are just trying to live out our highest ideal of what it is to be human here on earth and somehow integrating spirituality into the fabric of our every-day existence.

I think that’s what Peggy was getting at when she created this project.

Perfect! I was first introduced to A Song of Peace (Finlandia) on the Winsor Music series, and now I use that hymn all the time with my church choir. Songs For The Spirit has a ripple effect; Music is one of the very best ways to spread the message of peace and and all of the other goodies we crave.

It sounds like you’ve got quite a bit of work out there! Can we hope for some sort of collected, easily accessible body of what you’ve written?

That’s what I’m hoping to do this year, actually, is get all of these shorter-form works into one handy book. It’s been fun over the decades to see how my writing process has changed - hopefully I’m getting a little better with each song.

Speaking of learning and improvement, you are programmed on this concert with one of your professors from the New England Conservatory! Can you talk a little about what that’s like?

To be on the same program as Professor Heiss is a great honor, because he was one of my very favorite teachers at the Conservatory. I studied Twentieth Century Music with him. He was an inspiring, invigorating, and refreshing teacher... brilliant, articulate, kind and very approachable. He made a difficult kind of music that initially seemed intimidating very accessible. He piqued my interest in twentieth century music to the point where I started writing some of my own!

*The “square” referenced here is the traditional seating arrangement for Shape Note singing. A square is constructed using one or more concentric rows of chairs in which all singers are seated, including during performance. One singer traditionally stands in the center of the square to call the next song and lead it by keeping time, very simply in two beats, by raising and lowering their hand and forearm. The square is central to the distinctive sound of Shape Note because there is a dramatic acoustic difference between being a participant, sitting in the square, and an observer, standing well outside of the square. One cannot really attend a traditional “sing” as a removed observer in the way that classical audiences do because one cannot really hear the music unless one is in the square; even the word used to refer to occasions of Shape Note music-making is indicative of this complete breakdown between audience and musician. There are no performances, there are only “sings.”